The Silence of Holding In

I’ve been thinking about the silences that we learn to hold and what they say about us, what they condition us to expect, and to be.

As the name of this Substack can attest, I’ve been thinking for a long time about silence and how it has shown up in my life. There is so much depth and variety to silence. In a way it has a language of its own. There is the calm, contented silence of drinking tea on a snowy winter day. There is the tense, vibrating silence after a disagreement. There is the silence of swallowed words and feelings, choking in the throat. There is the longed for silence amidst noise and overwhelm. I’m sure there are many, many more. These are simply the ones that come up for me, today and many days. This post is an initial meditation on the silences in my life, perhaps I’ll write more. I would love to hear about your silences in the comments.

I’ve been thinking about the silences that we learn to hold and what they say about us, what they condition us to expect, and to be.

As a child I was told frequently that I talk too much. This “humorous vignette” is still brought up by my family. I was enthusiastic about life and wanted to share it, but somehow my expression was too much. Now the voice of Elyse Myers comes to me and says “Tell them to go find less.” But as a child I simply felt a hot flush and tried to talk less, sometimes holding my mouth shut even when I felt my belly would explode with the words I wanted to say. The yearning panic I felt at extended family dinners when conversation leaped quickly about the table and I could never find a pause large enough to get my words in. What I wanted to say was never important enough for them to pause for.

Now as a thirty-six year old, I have written “be like the birds singing” on the inside of my medicine cabinet door. All day the sparrows that live in my hedges call “I’m here, I’m here, I’m here.” Or maybe it's “This is mine. This is mine. This is mine.” They usually sound as if they are bickering. I posted it as a reminder to be noisy, to claim space, to express what I yearned to say as a little girl, and, perhaps more importantly, what I desire to say with the wisdom I’ve earned at this point in my life. It’s not the first time I’ve been trying to learn how to speak freely.

When I was two or three years old, I began to stutter. Scientists have not pinpointed why some people stutter. I do not really believe it is because I was told I talked too much. My first grade teacher thought it was because my parents “forced me” to read books that were too old for me. I was an early, avid reader of my own accord. But here I was again faced with a kind of silence, one that I could not control. My stutter is an inability to express my thoughts fluidly because the sounds get trapped in my throat, pulses of air echo and repeat the sounds (this is called blocking). While my mouth, tongue, and vocal cords seem frozen, my mind races trying to remember the trick to calm my throat, unstick my lips, and make the sound come out smooth like the speech therapist had taught me. Trying desperately to find another word that would fit what I wanted to say, that I could say right now. And thoughts of shame, of anxiety, of how others must think less of me because I am less fluent, must think I’m stupid because I have to replace the word I chose to say with a less effective substitute.

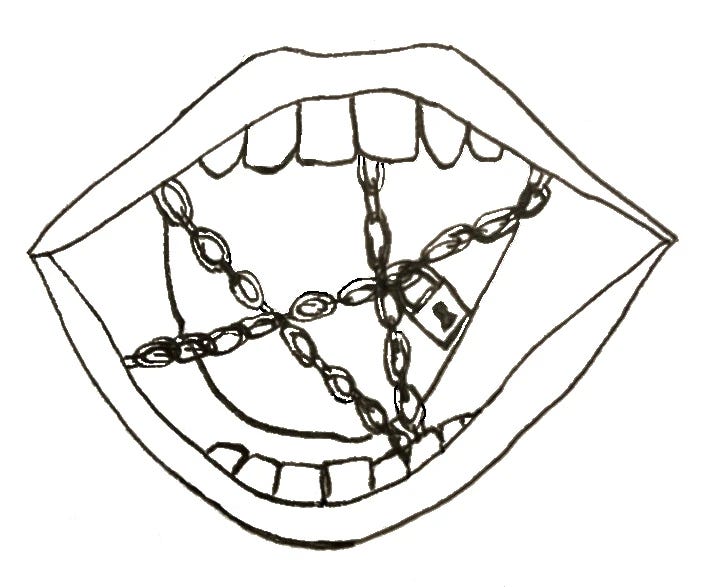

My body mars and silences my expression, my enthusiasm for life. That is how it felt for most of my child and young adulthood, that is how it still feels now, sometimes. Even though I kept my self-esteem during those early years, I was learning to be silent. I was learning to hold my tongue. My tongue was holding itself captive as it disobeyed my brain’s messages to form certain sounds. (This may not be an accurate representation of what is going on neurologically during a stutter, but it is what it felt like to me.)

Despite this I wasn’t a quiet child (as noted above). I hated reading aloud in class, but among friends and family I didn’t mind my stutter too much—unless my mother reminded me to “start over and take your time.” I wanted my enthusiasm to come out, I hated calming it.

I learned tricks to make it easier. I spell my last name before saying it to anyone who asks my name, especially over the phone. I avoided reading aloud and changed words in my speech as much as I could. I would laugh off my stutter as if it was nothing to me. (Narrator Voice Over: It was never nothing.) I was fortunate enough to avoid severe bullying about my stutter, so I did not recognize the negative emotional effects of my stutter until much, much later, as a young adult when the pressure to perform in graduate school made me second guess myself. The confidence I managed to hold on to as a child was now gone.

Class presentations became torturous as I went 10 or 15 minutes over the time limit, shame burning through my body. I would finally return to my desk, trembling and desperately trying not to cry. The thing about a stutter is once you start blocking, as you’re anxiety ratchets up, you block more and more, like a self-defeating loop.

At this point in my life, more and more of my thoughts and feelings lived lonesome within my head, with only each other for company. I held back from the people in my life. My fear of being too much, too enthusiastic, too difficult to understand kept me quiet, made me feel like an outsider, even when I was the only one labeling myself as such.

There are two cliche sayings that have stuck with me since childhood. One is said by Thumper, a rabbit, in the movie Bambi, “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say nothing at all.” The other was first heard in a Sunday School, the golden rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” These two phrases became my moral structure without me even realizing it. These two phrases both invite silences. I was praised for such silences.

A girl scout troop leader nicknamed me “Katie Didn’t” because I was mostly quiet when we were meant to, stayed out of trouble and followed the rules. She had to differentiate between me and another Katie who was more rambunctious, “Katie Did.” I don’t remember much about being part of that troop. I don’t remember this other Katie at all really. I wonder how “wild” she actually was. I feel envy, in retrospect, over her ability to stay loud.

I see now how my inner Thumper contributed to perfectionism. If I couldn’t say something right, if I couldn’t do something right, than I didn’t do it at all. I have missed out on so many opportunities because I feared I could not do it right. I became silent in my actions as well as in my words. I’m still fighting to override this habit. Choosing the name Stutter Over Silence for this Substack is, in itself, a reminder for me to speak imperfectly rather than stay silent, to write imperfectly, to draw imperfectly. To allow myself to be in the world as I am and not make myself invisible because I am not who the disembodied specter of “they” expected me to be.

As an adult, I am the primary caregiver to my two young children. I am starting to notice the silences I take in that role. All of the moments where I hold my tongue, and who benefits from those silences.

When it is the end of the day, I am exhausted and frustrated as the kids play instead of listening to my entreaties to go back to bed, sometimes I am silent. I feel the heat of a fire swelling up inside of me and I know that nothing good will come out of my mouth. Hearing my inner Thumper, I instead shut down, keep my mouth closed, my face as flat as possible, sometimes I go about my routine ignoring my children playing around me. I do this until the fire is quelled enough that I can usher them to bed, hoping that they will follow along because I’m not sure I can quell the fire again if they add more fuel to it.

Another example of this silence is when I hold my tongue around my partner. Perhaps he is stressed at the end of a long working day and the kids did something to create a mess or accidentally punched him and his frustration rockets off with a yell. I have learned that he does not like me “butting in” by suggesting another route to solving the problem or translating his feelings and desires into words the children will understand, so I remain silent. I watch it and try to remain calm, knowing that one way or another they will work it out and then, if needed, I can smooth out the pieces. (I do see the traditional female emotional labor I am assigning myself here.)

With motherhood, I realized how often I silence my emotional responses. I swallow them and hold them in my throat until the fever pitch passes. I see how I’ve done this before I had children, especially with friends or previous partners. Parenthood just brought it all to the forefront. It made it glaringly obvious.

My oldest daughter has inherited my talkativeness. From a year old she could talk constantly, ceaselessly. I never realized that I could be overstimulated by sounds until I had children. I searched out ways to cope, like tuning her out. Before the pandemic, I had an effective method: taking her out of the house. My daughter never stopped talking at home, but she was very shy and introverted around others, so when it got to be too much I suggested a walk to a neighbor’s house for a play date, or a library story time. Yes, such outings are good for her, but really they were so I could enjoy some quiet, a break from her constant attention and attention seeking. I wonder how else I’m manufacturing my children’s silence. I wonder how they experience it.

I also think about how my silences are perceived by my children. This stoicism I sometimes inhabit as self-preservation. I see now how this could be linked to my father—always quiet, almost never expressing his thoughts, stoic when arguments fly around him. I wonder if he, like me, is roiling inside in these moments. I was told once that his father was abusive. I wonder if my responses, or lack of responses, are some sort of inherited trauma. How can I know if this silence is a healthy coping mechanism, a vestige of trauma I am passing down to my children, or the indoctrination of a patriarchal society? Perhaps it is all of the above.

I wonder one day, will my children someday yell at me, hate and sadness in their eyes, asking why I was so cold, when they were so little and just needed my attention? Then the golden rule flashes before my shame-filled brain: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Do I want to be treated with silence? Ignored when I’m seeking attention and love? What does this silence say about me? What am I conditioning my children to expect? What am I conditioning my children to accept?

I know these questions come from the same place my perfectionist inner critic inhabits, but there is a kernel of truth in the answers. The only thing I can do is try to be reflective about my life and my behavior and try to use what I find to course correct going forward, even if it's a constant, gentle push back toward the goal, like driving a car that’s out of alignment.

I’ve been sitting with this essay for a while. Avoiding it. Knowing that if I dug deeper and spent more time on it… if I divided it up into a series, it would be better, more interesting, more polished. Instead, I’m leaning on my new reminder— Stutter Over Silence. I’m publishing it because that’s better than sitting on it forever. I can always say more later. That’s the amazing thing about breaking out of silence, there’s suddenly always more to say. It’s the opposite cycle of blocking during a class presentation. Now the more I say, the more confident I feel to say more.

Where have you silenced yourself in your life? What can you do imperfectly now rather than waiting for it to be polished?

All images published in Stutter Over Silence are original artwork created by the author, Katie Gresham, unless otherwise noted.

Languages of silence - yes! Now that I’ve read this I realise I have not reflected on my silences as much as I thought I had. It’s also a recurring theme of mine but I realise I haven’t explored it all that expansively. I relate to a lot of this. I want to go think and reflect on this a bit more. And I love the mum illustration with the toys - it’s just has something!

this is such beautiful self-reflection - I'm so glad you shared ♥️ and I have the sense that there's hundreds of other essays that could stem from just this one! there's so much to say about silence, and speaking up.

I rarely hold my tongue, but I can say from that perspective, I'm often scolded for my words; so I actually have very similar feelings about situations that spark my feelings, my thoughts, my words. interesting to think about it that way!

(and your words of wisdom are SO familiar. they were the boundaries around my childhood, too. I've been thinking a lot about "if you don't have something nice to say..." because then, how will change happen? the necessary kind? why is dissonance in relationships "bad"? why is the priority "keeping the peace" when we clearly don't feel internally peaceful doing it this way?)

xx

glad you're on Substack, sharing your Soul ♥️♥️♥️